This quintessential idea brings to mind one of my favorite quotations in a fantasy book series I recently finished called The Shades of Magic trilogy by V.E. Schwab (if you like edgy fantasy - a MUST read! The series begins with A Darker Shade of Magic). Lila, one of the central characters told another, “‘I’d rather die on an adventure than live standing still.’” And isn’t that, in many ways, a truth for all of us?

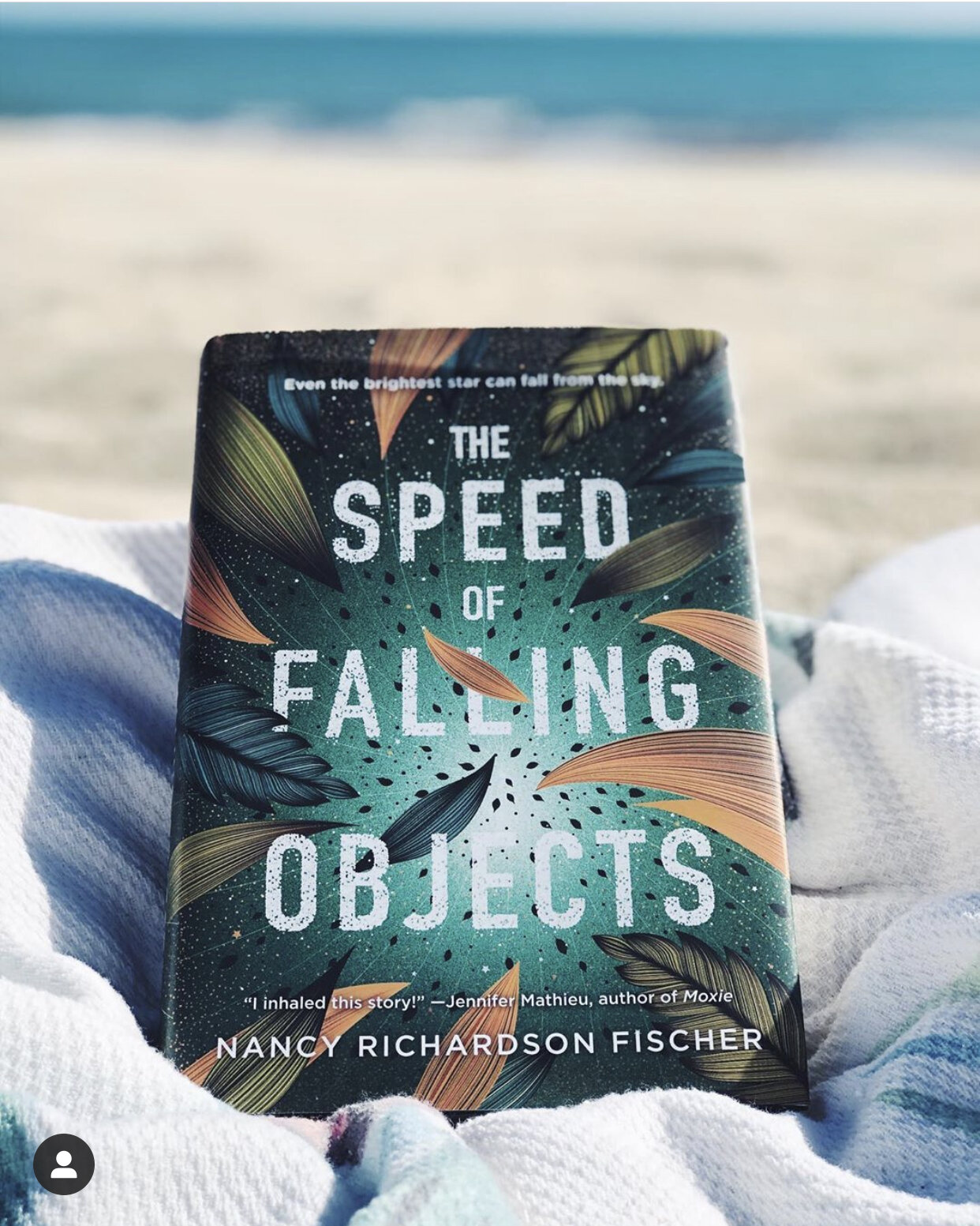

One amazing adventure story I wanted to share with you is The Speed of Falling Objects written by Nancy Richardson Fischer (her novel When Elephants Fly has been nominated for the Leslie Bradshaw Award for Young Adult Literature). It is not only a survival story but also an incredible coming-of-age tale swirling with family drama and new love.

Danielle (Dani) Warren, the daughter of a TV reality survivalist, is nothing like her brave father. After an accident that takes her site in one eye, she’s learned to compensate for that change, but that isn’t the only thing she’s compensating for; she wants to make everyone else happy, especially her mom, but it’s beginning to feel like it’s at a cost to her own. When her dad, who she hasn’t seen for years, calls to invite her on a trip to the Amazon to film the next episode of his TV show, she jumps at the chance to prove she can be the daughter he’s always wanted. But nothing goes as planned. When their small plane crashes in the Amazon and a terrible secret is revealed, Dani must face the truth about her parents, about her own happiness, and find the strength to survive the deadly rainforest to find her way home.

I loved this story, and over the last several months, I have had the wonderful opportunity to get to know Ms. Richardson-Fischer through Instagram (give her a follow @nanfischerauthor). She so graciously agreed to answer my questions as a contributor to the Reading Wonderland:

CLW: The Speed of Falling Objects is a survival story set in the Amazon. I have read on several occasions your aversion to reptiles and creepy crawly things. What on earth inspired this story?

NRF: I’ve always been fascinated with stories of survival—sinking sailboats and months lost at sea, climbers who help each other crawl down mountains after brutal injuries—there is no better way to figure out who people are, at their core, then to witness them struggle and see who retains their humanity, survives and thrives. Usually, it’s the person you least expect that digs deepest and surprises!

Originally the plane crash in this novel was going to happen on a snow-covered mountain. I’ve spent time winter camping, used to rock climb, and understand that world. But while doing research, it became clear that nothing would push Danny toward growth more than the Amazon.

There are 3,600 species of spiders in the Amazon Basin, 2.5 million insects, and seventeen types of highly venomous snakes. Plus, there are so many ways to die! If the plane crash doesn’t result in devastating injuries, a bite from a wandering spider can kill in less than twenty minutes. The fer-de-lance, an aggressive pit viper, has venom that leads to gangrene, amputation and death. Even the frogs exude a toxin that can cause fatal heart attacks. There are bullet ants whose bite feels like a gunshot, bloodthirsty leeches and electric eels that can unleash over 600 volts …

All of which I studied with shudders (Danny and I have that in common) as I squinted at photos, read first-person-accounts and watched survivalist videos. Choosing to create a character that has similar fears, at least in the creepy crawly realm, allowed me to identify and empathize with Danny and tap into my own very real fears to make hers more believable.

CLW: When writing this story, what was the scariest thing you researched and how did you get through it?

NRF: The scariest things were the spiders! Seriously, I am less afraid of a plane crash, broken bones and other injuries, sleeping in the jungle, even scorpions and snakes, than I am of a spider. But spiders came with the story and over time I was able to not just read about them but look at them so I could realistically describe their furry, terrifying bodies. For the record, in real life I’m still petrified of them.

CLW: There are a lot of things I loved about this book, but here are two: the way you delved into family relationships and its impact on identity, and the real way teens have feelings (especially with respect to sex and relationships) and how you didn’t shy away from either. Can you comment on what helps you explore those kinds of heavier topics with depth and realism?

NRF: The best way I know to explore heavy topics is to do the research. I read about dysfunctional families, used my own experiences in that realm, talked to teens, watched videos, read other books that dove into dark subject matter and then did my best to respectfully explore all the issues that Danny faces.

CLW: The Speed of Falling Objects is your fourth book and the follow up to the YA, When Elephants Fly. Having been through this publication process, going to book signings, interacting with readers, what was the most surprising thing(s) you have learned going through the process?

NRF: The Speed of Falling Objects is actually my eleventh published book! My first eight were sport autobiographies that I co-wrote with athletes like Monica Seles, Nadia Comaneci and Apolo Ohno. I also wrote three Junior Jedi Books for LucasFilm and then wrote When Elephants Fly followed by The Speed of Falling Objects. There have been a lot of surprises along the way. First, it was a much longer process getting to the point where I could write my own fiction than I imagined. Second, I’m surprised at how much I love the editing process—that’s where the real magic happens! Third, interacting with readers, doing books signings and meeting other authors has been both a joy and much needed. Writing is a solitary process so hearing from readers who love my books feeds my soul and talking with other authors provides a much needed group of friends who both support each other and help ease the rough patches along the road to publication.

CLW: Which is the favorite book you’ve written, and why is that the case?

NRF: I really don’t have a favorite! I loved writing Lily and Swifty’s stories in When Elephants Fly and the chance to educate people about the plight of elephants, but then along came Danger Danielle Warren in The Speed of Falling Objects… Each book I write is my favorite of the moment. And then I move on and give my heart to the next story.

CLW: What is your favorite genre to read, and do you have a recommendation for readers?

NRF: My reading is all over the place. I love all of Tana French’s mysteries—she’s a poet at heart and creates incredible characters. I can’t put down Stephen King’s novels and am dazzled by his imagination and the way he makes me care. And Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale has stayed with me for life.

CLW: Favorite classic read?

NRF: For Whom The Bell Tolls by Ernest Hemingway.

CLW: Stephen King wrote that “Books are distinctly portable magic.” What was the last book you read that transported you?

NRF: Mary Doria Russell’s The Sparrow changed me forever. Then I read her follow-up, Children of God, and I was changed again.

CLW: Which specific authors or specific books - YA and otherwise - have inspired your own author’s journey?

NRF: Too many to name so I’ll just list a few of the authors I love… Misa Sugiura, Jennifer Longo, Jennifer Mathieu, Frances Hodgson Burnett, Stephen King, Peter Straub, Rebecca Makai, Mark Helprin, Sara Blake, Diana Gabaldon, Barbara Kingsolver…

CLW: The theme is YA Contemporary books. What makes your top-five list in no particular order?

All the Bright Places [by Jennifer Niven]

A List of Cages [by Robin Roe]

The Outsiders [by S.E. Hinton]

The Hunger Games [by Suzanne Collins]

Lord of the Flies [by William Golding]

CLW: What are you working on now?

I’m working on my second adult novel! It’s an exciting new world and I hope that the readers who loved When Elephants Fly and The Speed of Falling Objects will take a chance and give my next novel a try!

CLW: Where can readers find you?

Readers can find me on Instagram and Twitter @nanfischerauthor and can write me at: nancyrichardsonfischerauthor@gmail.com. For all requests, please contact my agent, Stephanie Kip Rostan, Levine Greenberg Rostan Literary Agency.

So much thanks to Ms. Richardson-Fischer and the time she offered to share with us!

Next Week: Piper Bee and her upcoming release,

Joy’s Summer Love Playlist