3 Things I Learned About Reading Space Opera

I made mention of sci fi and dystopian in an earlier post (click here for that), but I’m circling back specifically considering the space opera. As a definition, space opera as a category is a story set in outer space that is typically simplistic in nature and dramatic. The most famous space opera: Star Wars. Nebulous futures, scientific explanations about flying through space, the end of the human race, robots, artificial intelligence, heroes who need to save the day. You get it, right? And with my focus on The Ring Academy: The Trials of Imogene Sol—which is most definitely a space opera—and its impending release, my mind is a bit preoccupied in this category.

So look…a lot of the same lessons I’ve mentioned from earlier posts apply here, but rather than be repetitive, here are three new ideas to twist the lesson which can be applied to any category of writing.

Asking the Right Questions

Read any info heavy science fiction novel (ah hem… Dune…) and you’ll understand that just like a fantasy story, it’s easy to get caught up in the minutiae of the information that defines the story. The problem, of course, is information dumping and information overload (which I’ll cover in a moment). This turns off most readers. What great writers in the category do well is parcel out information that is relevant to the necessary questions. Of course a reader has questions about the world, but not all the questions are necessary to the story. Not all of them fill in the gaps of the plot hole. While the author has a lot of the questions answered, that doesn’t mean the story needs all of them answered. The trick is identifying which ones need to be answered for the sake of the story.

One of my favorite dystopian writers is Paolo Bacigalupi (Ship Breaker, The Drowned Cities, and Tool of War). The cool thing that Bacigalupi does that I’ve seen some of my favorite fantasy writer’s employ is drop the reader right into the world and unfold the world around them as if the reader is already a member of the society. I LOVE this technique. A perfect literal example of this technique is The Maze Runner by James Dasher. The reader is Thomas dropped into the maze having to learn on the fly what’s what and how he fits in. The pros of this is that you avoid the pitfall of the info dump, and like the character, the reader uncovers the world and the conflict as they go.

There is inherent danger in losing the reader when an author embarks on information overload. I get the temptation to include all the cool things developed in world building, but just because it exists, doesn’t mean it’s relevant to the narrative arc. Well-written books in this category recognize this and employ an “as needed” methodology by understanding which questions need to be answered.

Which leads to the next point…

The Structure (the world and creatures)

Space opera (which encompasses Sci Fi/Dystopian) writers build worlds like fantasy writers, but then they destroy them. There is a methodology to this madness of course, even if they make it look effortless. But then consider that a wonderful fantasy story’s world is important to overall conflict from political machinations to traditions and systems impeding a hero’s journey. In Sci Fi/Dystopian the structure of the world and its demise is often the narrative architecture around which the conflict is built.

It’s clear when we enter habitat with Mark Watney in The Martian by Andy Weir, the structure of not only the immediate place is a functional place, but also that as a reader, the structure of the story is about survival. We are surviving with Mark, we are invested in his success, in the tension between learning he will connect with NASA. Or as we siphon through the missives of World War Z, the means by which author Max Brooks structured the novel makes it necessary to understand the hows and whys and what-fors in order to understand the movement of the narrative. The world, the creatures (think Alien) are so integral to the story, they can’t be removed or changed without impacting the overall narrative structure becoming a character in and of themselves.

Which then leads to:

Reader Story Interface

It might be easy to develop a story in this category so high above a reader’s understanding that it becomes inaccessible. But strong writer’s of this category make sure that the average reader is as much an expert as the scientist character or the super computer. Isaac Asimov is a great example of this. A very talented scientist (physicist), he was a pioneer in the science fiction realm of writing, making science fiction accessible (check out his Foundation series).

And really, that’s what any category is about right? Making the narrative accessible to the reader so that they fall in love with the story.

My Trek...Journey...Quest to O'ahu Independent Bookstores

I love bookstores. LOVE THEM! It isn’t surprising for a bibliophile and writer, but for this Oʻahu resident—especially one that lives on the south shore—access to bookstores is problematic. With the closure of Borders in 2011, it left Oʻahu with a single, big-chain bookstore, Barnes & Noble located in Honolulu, and a smaller Japanese conglomerate called BookOff. So I decided to go on a trek…a journey… a quest (FYI, this must be said like Peregrin Took from Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings, the Fellowship of the Ring) around Oʻahu to look for independent bookstores. There is something magical about walking into an independent bookstore done right. They are imagination bottled between four walls with the possibility of discovering buried treasure.

So before you go on the quest with me, a comment on island living for context. Though everything as the crow flies seems close and the mileage between cities on an island like Oʻahu sounds manageable, the reality of trekking those miles is a production. During peak traffic, for example, to get the 20 miles from my home to Honolulu would take a minimum of an hour, give or take an extra 30 minutes, which means that a quick trip to a bookstore isn’t happening. There aren’t any bookstores in my area of the island, which means traveling to a bookstore is a necessity—including the single Barnes & Noble.

But this intrepid explorer was committed, and so off I went . . .

The first store I visited was Da Shop: Books + Curiosities located in Honolulu. An independent bookstore operated by small, independent publisher, Bess Press Publishing, it caters to Bess Press titles—mostly local and Hawaiian—with some niche national publications thrown in. It is a small shop, with a very curated front face along with a back warehouse for clearance titles. I loved that they have a true adherence to Asian Pacific Islander voices with a smattering of mainstream voices, all thematically connected to truly diverse author options. I enjoyed walking in the small shop and seeing so many AAPI authors.

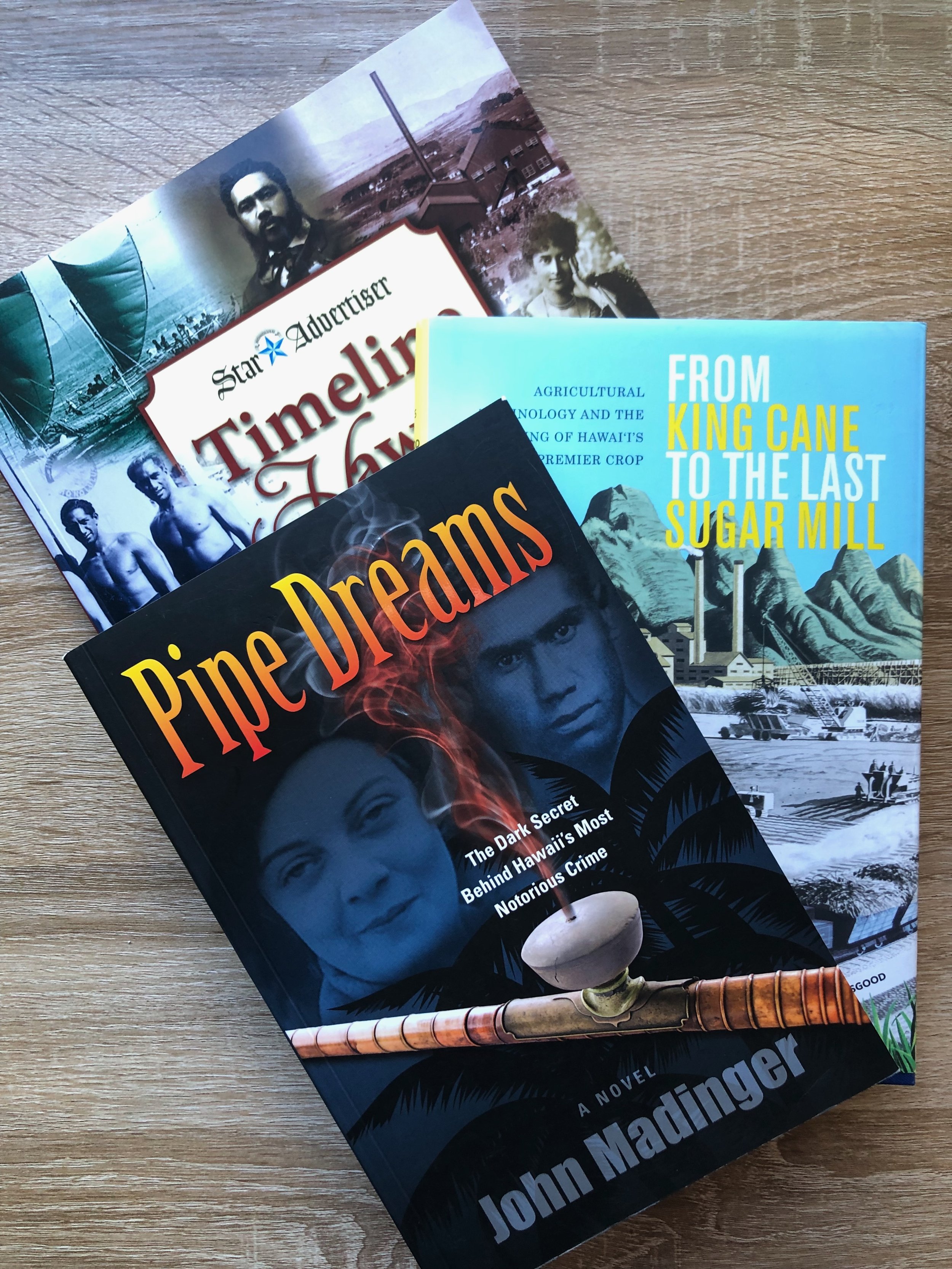

Idea Music and Books was the next location I visited. Also in Honolulu, Idea has been in business since 1976. The space is split into two sections: the front portion of the store caters to the new-and-used music with a plethora of vinyl in stock. Idea seemed like a dream for the music lover. It was organized and clearly marked. The back portion of the location is filled with books, mostly used titles with a smattering of new books. While they are shelved by categories, the organization is haphazard. If one is willing to dig for buried treasure, Idea had a treasure trove of older titles, and I found a stack of difficult-to-find titles on a particular subject I’m interested in researching.

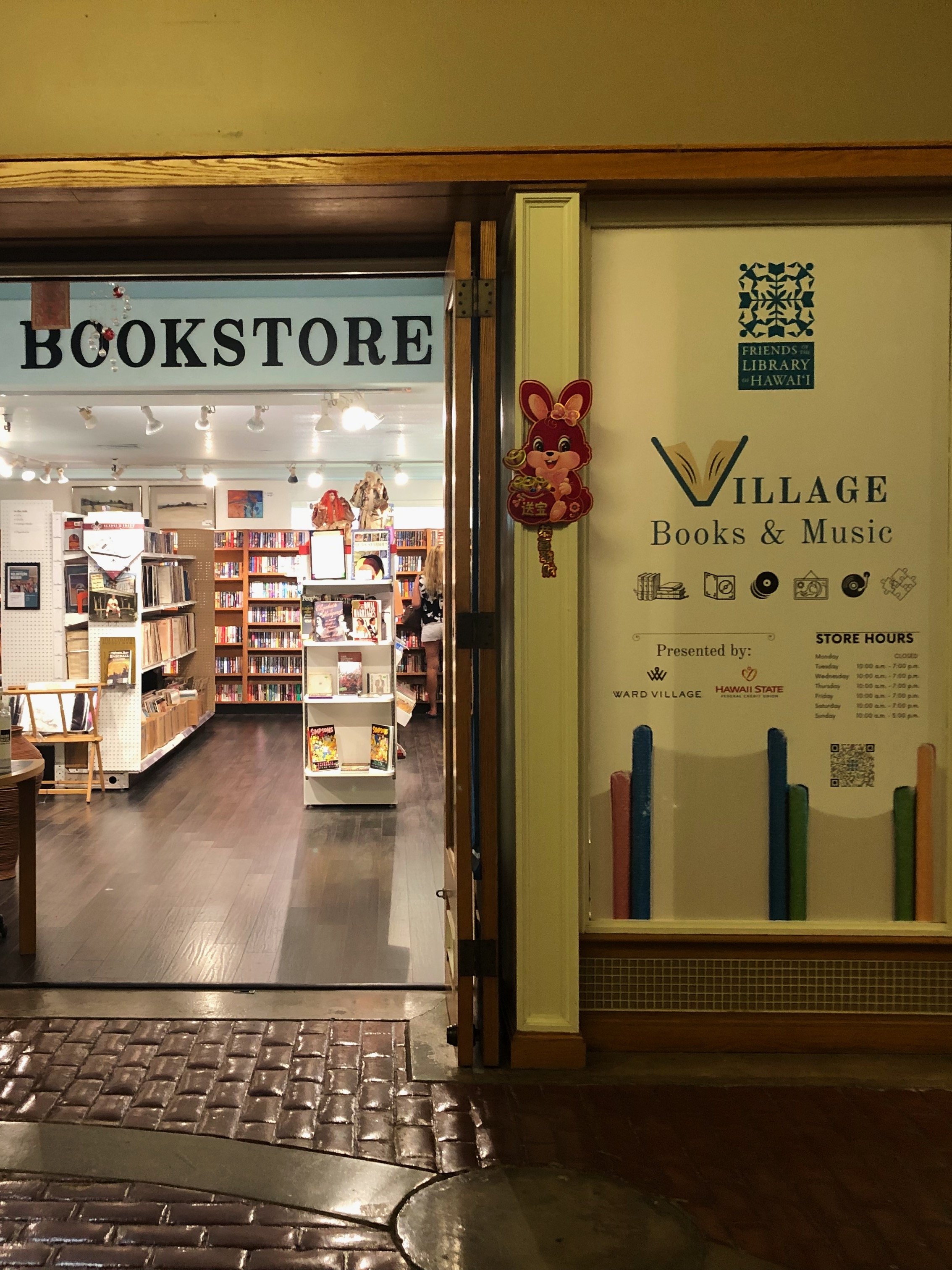

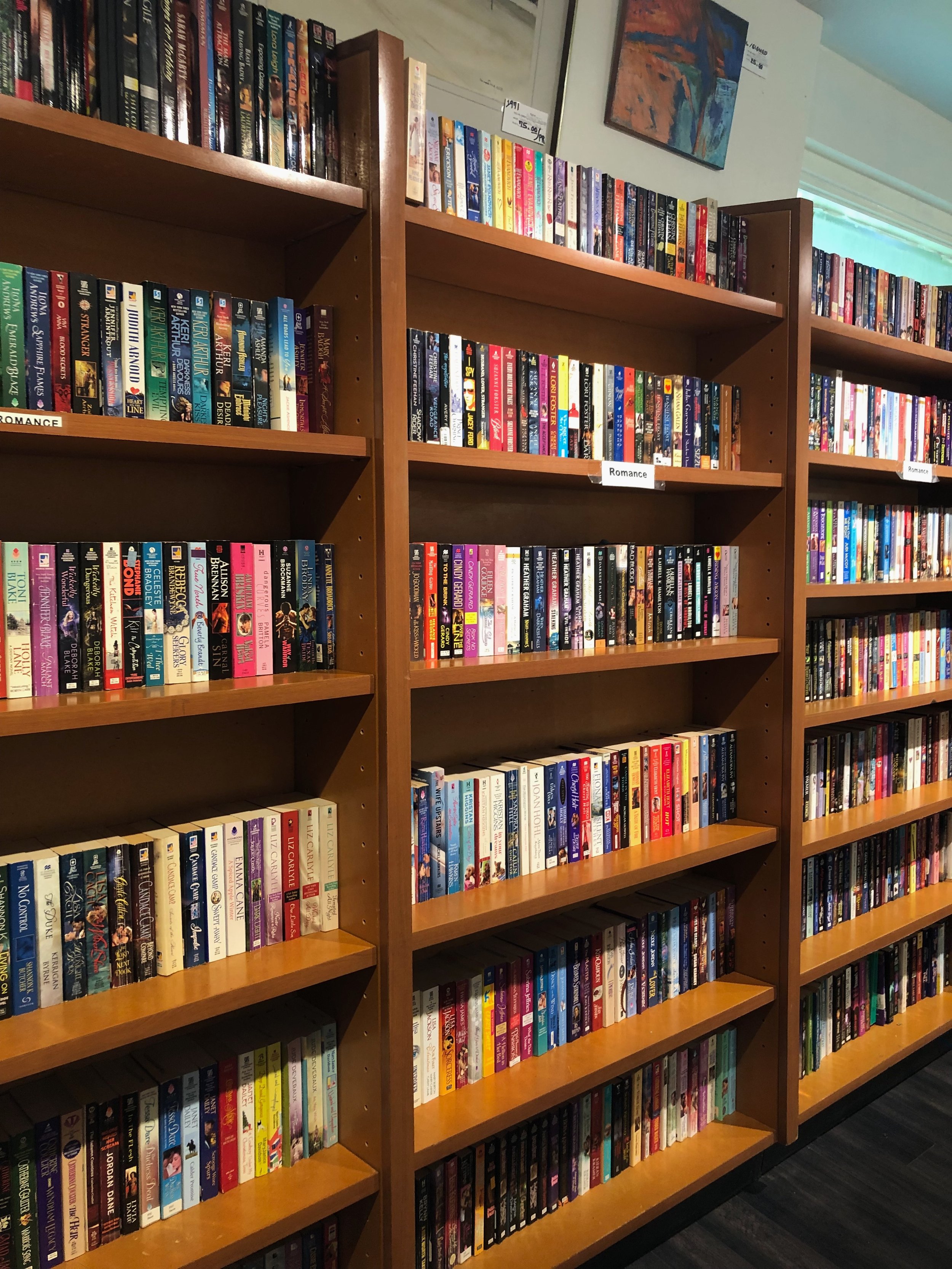

Deep in the hallways of an older mall with limited foot traffic is a hidden treasure, Village Books & Music, a “friends of the library” bookstore that supports Hawaiʻi libraries. As bookstores go, this one was the most “mainstream” offering all kinds of titles and organized nicely by category and author. I could have looked over the shelves for hours. The quality of the books are exceptional and the prices (at $3-$4) economical. I found a few newer YA titles to add to my collection (Nic Stone’s Chaos Theory, for example) and some nostalgic adult titles (Lavyrle Spencer, who was a favorite of mine in high school) to add to my collections. When I took my books to the cashier, I noticed she was reading The Count of Monte Cristo and we had a fun chat about reading as I checked out.

Next, I went to Na Mea Hawaiʻi, a Hawaiian culture shop that carries a curation of Hawaiian artisanal merchandise from art, to clothing, to beauty goods, to food items, and finally books that cater to a Hawaiian perspective of place and people. I had a wonderful chat with a salesperson who helped me look over the book selection, and we found a few titles to add to my growing Hawaiian collection. A beautiful independently owned shop, this wasn’t specifically a bookstore, but it had a lovely book section.

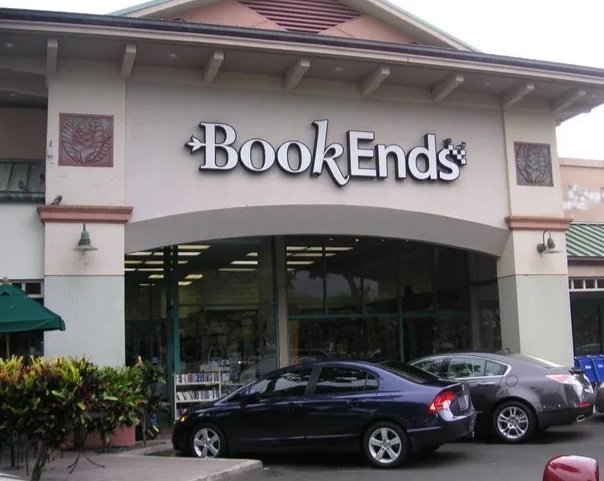

Please note: these images were taken from two previous articles written about Bookends: Here & Here

Located the farthest on my quest was BookEnds in Kailua. Independently owned and operated since 1998, BookEnds was voted the Best Neighborhood Bookstore by Honolulu Magazine. It’s a tiny shop filled to the brim with a new-and-used collection, offering a diverse collection of titles. I found a lovely, first US edition, signed copy of Witi Ihimaera’s Whalerider here. Boy, did I feel lucky! (And for kicks, this was the first independent bookstore on the island that supported me as an indie author by stocking my books).

There were a few more places I discovered but haven’t had time to visit in person yet. Skull-Face Books is a new independent bookstore catering to new-and-used books and vinyl, Arts & Letters Nuʻuanu offers native books and art, Logos Books of Hawaiʻi, niched to Christian reading, and BĀS Bookshop is niched to art and design. Additionally, I found there are a plethora of shops that carry books, though not exclusively, and several comics and manga shops on the island. Of all the bookstores I visited, only Da Shop, Na Mea Hawaiʻi and BookEnds specialized in selling new books.

As an average human, who really loves convenience (and whatever taxes my time and wallet the least), I made some observations about the experience of shopping at local, independent bookstores.

First, as much as I loved walking into these bookstores and enjoying the unique vibe of each, they didn’t always carry what I wanted. This isn’t surprising when the bookstore offers niched merchandise or is more focused on the “used” rather than the new. And of the stores that did carry the “new” books, they didn’t always have a book either. Of course, it’s unrealistic to think that a small, independent bookstore can carry every title. While I could have used the trip as an opportunity to order that special title from the bookstore, the reality that I would have to make a “trek” out to the bookstore again, using time and resources to do it was off-putting.

While digging for buried treasure is fun, I don’t always have the time for it. Sometimes, I just want to walk into the bookstore, find a book I’m looking for, and walk out. Books are already chaotic, so when it’s difficult to find books, it can make the experience overwhelming.

Finally, there was very little diversity between traditionally published books over independent titles. Aside from the niche stores, the new-and-used stores adhered strongly to old mainstream offerings of bestsellers being resold. Besides Na Mea Hawaiʻi, which offered new independently published Hawaiian titles, I didn’t see any independent authors offered in the other shops.

Here’s an interesting fact for you: I didn't find any of my 11 titles on the shelves in any of my local, independent bookstores. As an independent author, I have contacted most of these bookstores to share that I am a local author, sent flyers with new releases, have offered to send the purchaser some books, and expressed interest in taking part in any author events. Two of these bookstores responded to my queries. One—Village Books—invited me for an author talk and the other—BookEnds—purchased my books for their bookshelves. Interestingly enough, it was my local Barnes & Noble bookstore that reached out to me interested in carrying my titles and invited me for a signing. Granted, this is just one author’s experience, so keep that in mind. And it is important to remember, bookstores are businesses trying to turn a profit, so taking risks on books with no guarantee to move is risky… but that’s an entirely different post.

My Life as an Alien Invader

And all the Oversimplified Gists

Before I met my husband or moved to the Kingdom of Hawai’i, my knowledge about it was rooted in the gifts my grandparents would bring back from their visits: the touristy plastic lei and the “hula” girl doll that rocked back and forth decorated in the grass skirt and coconut bra. I knew it was really far away and that my grandparents had to take an airplane to visit. My young brain understood it by the exotic perpetuation of stereotypes reflected in the media. I remember Magnum PI (the Tom Selleck version), the Brady Bunch visiting Hawaii, and Saved By the Bell: Hawaiian Style, for instance. These stereotypes shaped my understanding about Hawaiʻi.

The first time I ever visited, technically, I didn’t journey here as a tourist. Instead, I visited Hawaiʻi as a guest of my boyfriend to stay with his family. Though he took me to see some “touristy” things, I got to experience Hawai’i immersed in the reality of living and working in this place. After getting married to that boyfriend, I moved here, but it didn’t connect that I was moving to a place illegally occupied by the United States. Truthfully, in 1997, I didn’t think much about it at all. I had just married my Hawaiian husband, who I just assumed lived in the fiftieth “state”. It had only been 100 years earlier that Hawaiʻi’s Queen Lilioukalani was held prisoner in her own home and forced to sign a “treaty” which eventually led to Hawaiʻi’s annexation as a US Territory in 1898 and was ratified as a “state” in 1959.

But this isn’t what we’re taught about Hawaiʻi on the mainland.

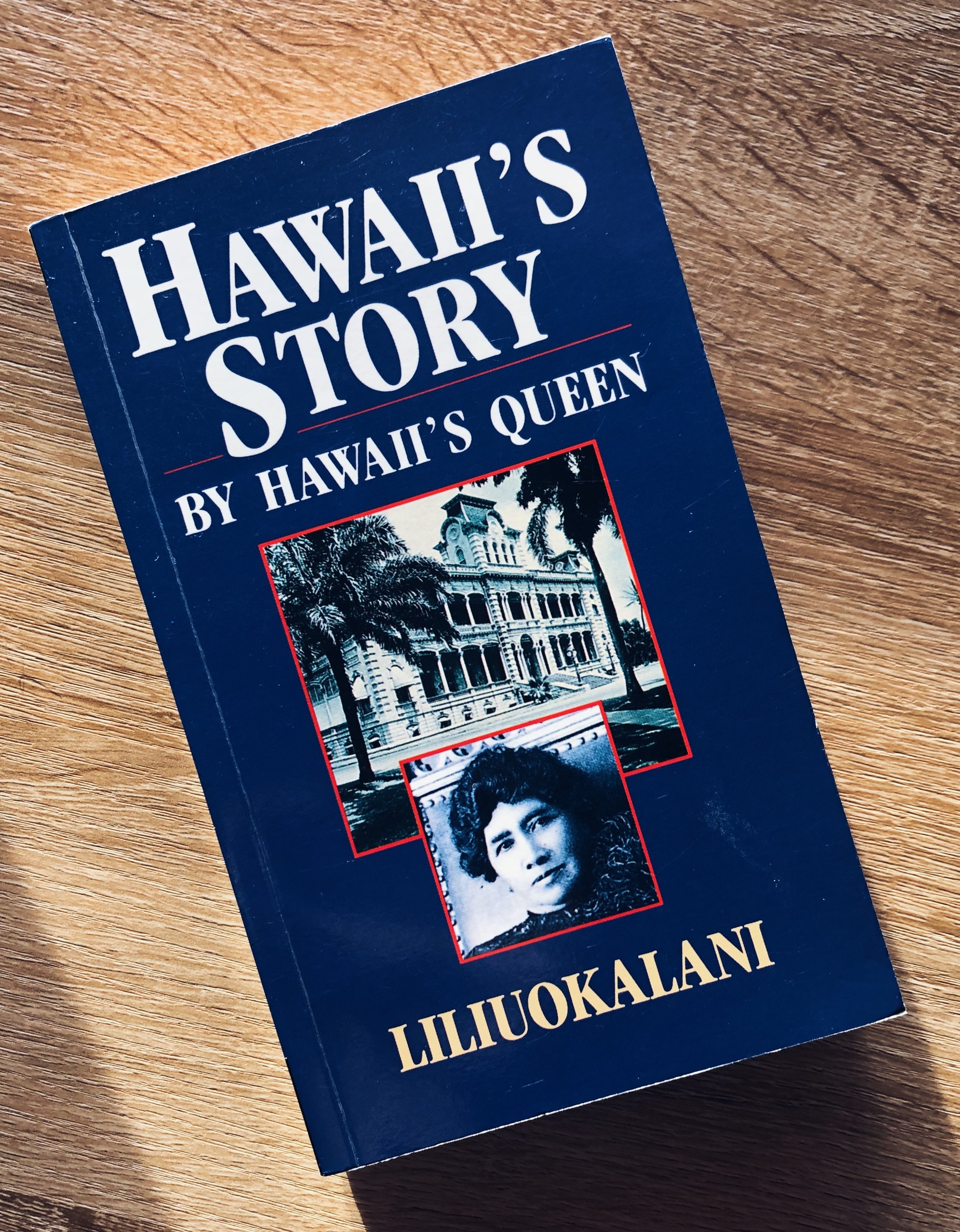

The oversimplified gist of those events is that a group of white, American businessmen descended from the white, American missionaries, who settled in the kingdom—in order to protect their business interests—leaned heavily on the queen to sign control of the kingdom over to the American government. When she refused to kowtow to their demands, she was seized and held prisoner in her own home until she signed the “treaty”. There are a ton of books written out there about it by people much more knowledgeable than me [and if you're interested, I would highly recommend starting with Queen Lilioukalani’s journal Hawaiʻi’s Story (1990)].

Unfortunately, there are more people like that 1997 version of me. Many people in the contiguous United States are unaware of the political history of the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi—it’s geographic isolation is just one reason it might not show up in a US history lesson, but let’s be real, that isn’t the only reason. I didn’t learn about it in school. Considering my own education in a rural area of Oregon, I barely learned about the native First Nation people indigenous to my own area (which I now know to be the Klamath, Modoc, and Yahooskin Tribes). My education about nonwhites (and keep in mind this was the late 1970s and 1980s—I graduated from high school in 1992) was filled with what I know now to be unbalanced content that perpetuated all the stereotypes, reinforced white bias, and the heroic propaganda of the Mein Kampf . .. oops, I mean, US History textbooks: Colonialism? What is that? Like settling the first 13 colonies to get away from religious persecution? Here’s the definition: Colonialism is when a country sends settlers to a place and establishes political and cultural control over it. So those missionaries that turned into land holders that turned into business men pushing their own religious and political agenda onto the indigenous population. Yeah. Colonialism.

I had this epiphany the other day that colonizers are like invading aliens. Now, please don’t align my use of the word “alien” with the way the United States right-wing has used the term to identify undocumented people trying to seek asylum and better conditions in the US. Not the same thing. My use of the word alien should conjure more of the War of the World sucking up human bodies as fuel connotation. And we love those movies right? Mars Attacks!, The Edge of Tomorrow, Independence Day, A Quiet Place to name a few. Each of these stories offer the premise that the human world is being infiltrated by an extraterrestrial, alien species bent on colonizing the planet (stealing resources, but same difference) and the people rise up and heroically fight against the monsters.

You see the irony right?

But know that this isn’t an essay on white guilt, but instead an acknowledgement of the reality of the state of things in Hawaiʻi. Nor is it an essay meant to perpetuate a xenophobic ideology. I wanted to offer a perspective of someone outside that indigenous perspective who IS the alien invader—albeit a welcome one, because there is power in sharing the truth of things. I am not Hawaiian. I’m a guest on this land (ʻāina), and it’s very important that I understand it, just as I hope I would of any place I visit.

Just as I hope that you, too, would understand Hawaiʻi on a deeper level when you visit.

I’m sorry to say there is no one more entitled than a tourist. On one hand, they’ve spent a lot of money on a “dream vacation” so they want their idealized dream, but on the other, they are occupying someone’s home where that dream isn’t real. A common thing I always hear from tourists is: People should be happy we visit. Tourism creates jobs and puts money in the economy. Okay. Get that, but let’s take a closer look. If you were to just take in the Hawaiʻi Tourism Authority data, you’d think tourism makes Hawaiʻi a boomtown. But just like my oversimplified gist earlier, that’s an oversimplified argument filled with unaccounted for nuance and context.

Here are some numbers for you:

The median income in Hawai’i is around $37,000.

The cost of living in Hawaii—in order to make ends meet—is listed at *$70,000 *though other sites have cited “to be happy in Hawai’i,” a household would need to bring in $195,000 (this is more reflective of an income with the ability to contribute to savings and retirement).

The median rent is $2,300

The median home price is $810,000 (which with a 20% down means financing $648,000) Do the math. Even making the $70,000 dollars isn’t going to get you a home.

Hawaiʻi’s minimum wage: a whopping $12.00/hour.

The average tourism job starts at $12 - $17/ hour. And you know . . . come on, you know… most corporations aren’t hiring workers full-time in order to avoid paying benefits, so people are working double, triple jobs to afford living and health care.

Those abysmal numbers highlight the average means for a resident of Hawaiʻi. While the Hawaiʻi Tourism Authority cites collecting upwards of $2.6 billion dollars in tax revenue, this money doesn’t impact the day-to-day lives of the average person in Hawaiʻi struggling to make ends meet. Then their resources (water, sewage, air quality, sea quality, food costs, housing costs) are tapped by the massive influx of invaders—the tourist—whose tourism dollars would have to be spent in Hawaiʻi owned business—Hawaiian owned shops, in Hawaiian owned restaurants, in Hawaiian owned boutique hotels, to actually benefit the people with their tourism money—but this isn’t the case. Most tourism dollars are spent supporting the conglomerates (chain hotels, chain restaurants, chain stores) who pay their workers minimum wage.

There’s the argument that assumes someone living in Hawaiʻi can find a job outside of tourism. Except it's a machine which means every family in Hawaiʻi is impacted by this industry. Even if the local population wanted to boycott tourism, they couldn’t. Do you think it’s the dream of those hula dancers to dance at the Hotel Luʻau? Case in point: my oldest child has a college degree and the only position that seems to be open after months of looking for full-time employment is a position at a hotel.

So here’s another oversimplified gist: tourists and non-Hawaiians accessing the land and resources are benefiting the bankroll of the businessmen. And those businesses are protecting their business interests—not aligned with Hawaiian ideals—and leaning heavily on the working-class of local and indigenous people who live here, who benefit very little in the day-to-day of their lives. I know Hawaiians have a lot more to say on this topic and I won’t presume to speak for them, but I know many who have gone so far as to say, “don’t come here without an invitation from someone who lives here.” If you think about it, that’s actually a great practice—that was my first visit to Hawaiʻi, remember? How much more do you appreciate and take care of a place when you visit knowing you’re guests of friends?

A few years ago—pre-2020—my husband and I had the opportunity to travel to Europe on a river cruise down the Danube. One stop in particular sticks out in my mind. It was in a small river village in Austria, and it was clear that the village was reliant on tourist dollars, but also that there was more to the town than what we could see in the six or seven hours of our stop. Most of the tour group—fifty or sixty of us—decided to go to a local winery. We sat in the tasting room and listened to the vintner tell us about his products, then we were given samples of the wine. It was a picturesque location vibrant with local flare. What stood out to me, however, was the way several members of our American group were behaving. They were loud, interrupted the man speaking, laughed loudly (and since there was a language barrier, one might assume they were being laughed at). I was mortified by their behavior, so ashamed.

Having been in Hawaiʻi now for nearly thirty years, I have witnessed this kind of behavior by alien invaders. The trash left on beaches, the entitled attitude about space because “do you know how much I paid for this vacation?”, the lack of regard for the real people taking care of them in service jobs. One time my husband and I took my visiting mother for breakfast on the beach. When we arrived at the restaurant, my husband approached the host podium to get on the list for seating when a tourist looked him up and down, then sneered as she said, “I was here, first,” to which my mother replied, “I think he’s been here longer.” The tourist didn’t get it.

And that is where the problem lies. Invaders and occupiers take. And even in spite of that, Hawaiian culture is all about hospitality and generosity. Nana Veary, Hawaiian spiritualist wrote in Change We Must, My Spiritual Journey (1989) about a lesson she learned as a young girl when her grandmother invited a stranger to come in and dine. She didn’t understand why her grandmother would feed him to which her grandmother replied in ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi, “I want you to remember these words for as long as you live, and never forget them. I was not feeding the man; I was entertaining the spirit of God within him.”

That gracious hospitality still exists in Hawaiʻi and is inspiring. I would argue that for that generosity to continue, there needs to be a reciprocal nature to the host-tourist relationship. Do you show up at your friend’s house empty handed? Your parent’s house? What about the brand new neighbors to the neighborhood? So here’s some food for thought: As an alien invader… ah hem…I mean as a tourist to Hawaiʻi (or any other place for that matter) what are you giving to the space that you occupy? Are you bringing anything other than your entitlement and your trash? Take some time and learn about the real place, the home, the land you’ll be occupying rather than fetishizing it and snagging the cheap, plastic hula doll you’ll stick to your car dash so you remember lying on Waikiki Beach that one week that one summer.

You can find this post and others on my SubStack.

How I Got to Hawaiʻi, My Hawaiʻi Story

In Honor of Pacific IslanDER Heritage Month

There are quite a few stories about people coming to Hawaiʻi to visit, then never leaving. Hawaiʻi is an amazing place, so I can understand the attraction (though I do have mixed feelings about it). My story, however, is a little different…

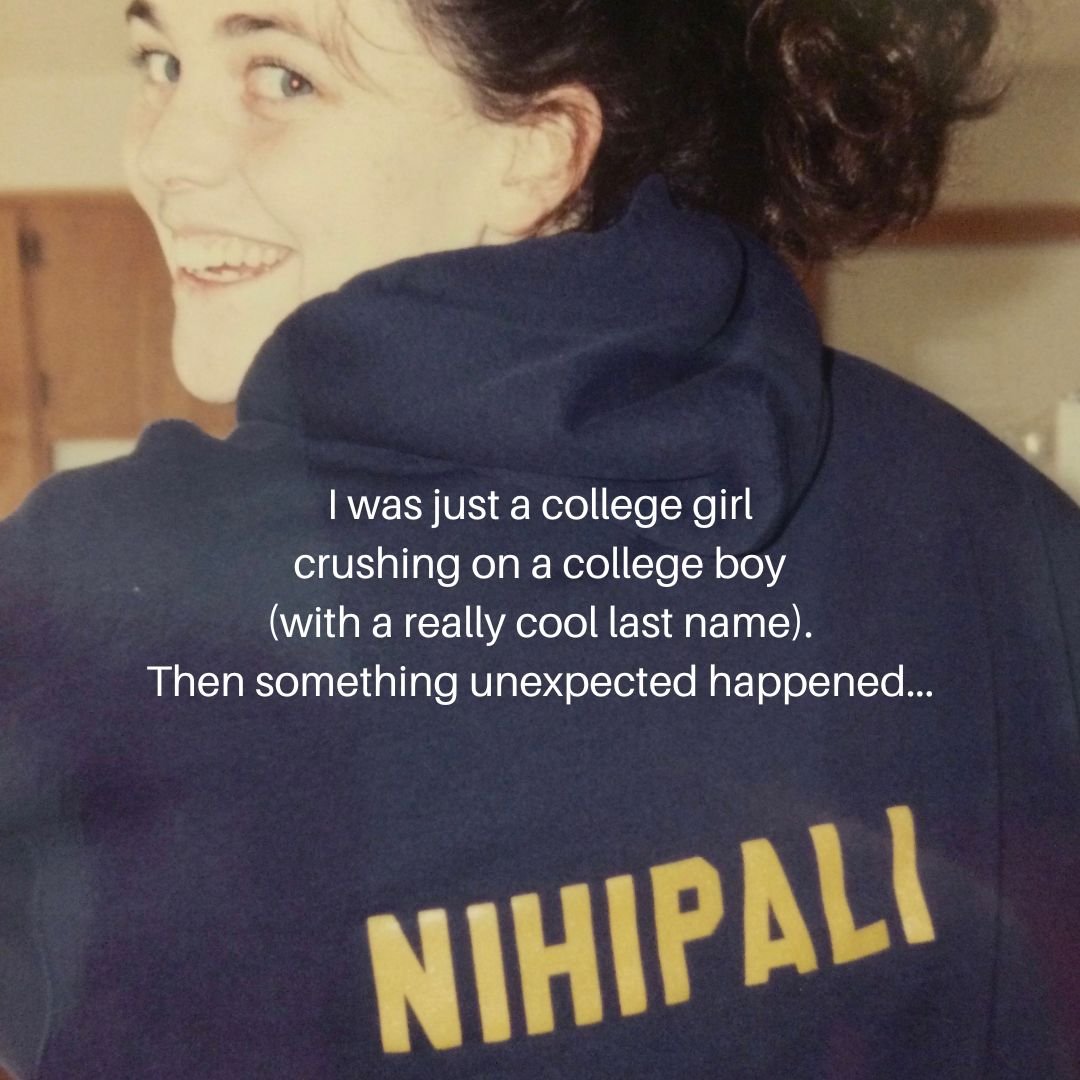

When I was eighteen, I went off to college. Ah hem. Okay fine. I didn’t even leave my hometown. I enrolled at my local college, started going to classes, and was well on my way to flunking out—yeah. I had no idea why I was there— when I met a guy. In hindsight, that exact reason was probably why I was initially there (which is a completely different story). His name was Vince, he played football for our college, and he was *Hawaiian from **Hawaiʻi.

*Quick lesson No. 1: I’m from Oregon. And as with most states in the United States, we tack on an -ian at the end of the world to indicate our state of origin. I was born and raised an Oregonian, for example. The same isn’t true for Hawaiʻi. People who live in Hawaiʻi aren’t indicatively Hawaiian, even those who were born and raised here. Hawaiians are a native group of people who are indigenous to Hawaiʻi. It’s disrespectful, then, to say that just because I’m from Hawaiʻi that I’m Hawaiian. I am not. The proper term would be to say I am “local”. For an interesting take on the origin of being a “local” in Hawaiʻi pick up John Rosa’s book: Local Story: the Massie-Kahahawai Case and the Culture of History.

*Quick lesson No. 2: I used to pronounce Hawaii as (Hah-why-ee). That, my friends, is incorrect. The correct way to pronounce this amazing place is Hawaiʻi (Huh-vī-ee—making sure that second sound—vī—is short and sturdy).

Long story short, after Vince and I dated, eventually making things exclusive, the school we were attending dropped the football program. Vince decided to transfer to play football for another school and suggested I transfer with him. I may not have known why I was in school yet, but I did like the guy. Why not? So off we went.

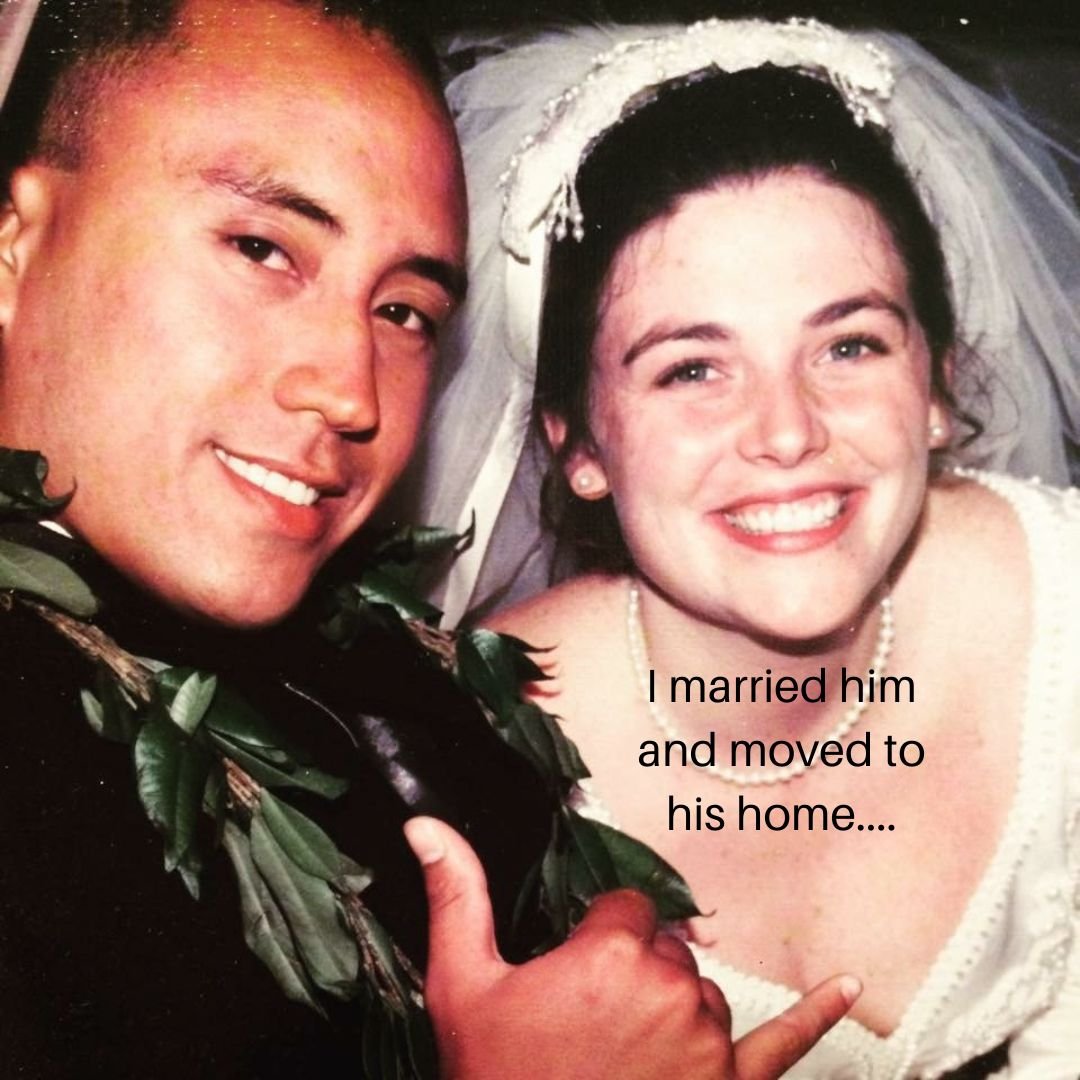

I did finally figure out why I was in school—majored in English—and we continued dating while we went to school. Our relationship turned into the five-year variety, and we got married in 1997. And then I moved to Hawaiʻi (did you say it right?) that same year. Married for nearly 26 years now, I’ve lived in Hawaiʻi longer than I lived in Oregon. I am so grateful to call Hawaiʻi home.

(You can find this post on Substack, here.)

You Can Go Home Again

You know that party question: would you go back to high school? It often creates an either-or dichotomy: Hell no! Or Absofuckinlutely! For the last eight weeks, I went back to high school. Okay, not as a student, but rather as a long-term substitute teaching English to 9th grade students. Given I taught English for over twenty years, this wasn’t a stretch, but after nearly three years outside of a traditional classroom working instead as a full-time author, it was a refresher in all things teen and work life. This, my friends, is what I learned returning to the classroom.

First, kids are kids no matter the year. Granted, the 13-and-14-year-old students I was attempting to impart wisdom about Shakespeare’s The Tragedy of Romeo and Juliet were eleven when they were forced home for Covid. So their sixth-and-seventh-grade years (a primary time in learning communication skills) were spent behind computer screens (and believe me it showed). I got them journals to decorate and make their own and each class we spent writing for the first ten minutes. Then—to practice our social skills—we “turned and talked” and like any teen, they fell right into that activity. It took a bit of time to get them to share with one another, but after a week or so, it began to feel safe, normal even. Teens are awesome people. They’re funny, they’re pragmatic, they’re focused (on what they’re interested in), and like all people, they're social.

Sometimes I get so far into my head, I forget the socialization part of life. I’m a self-professed introvert. I am content in my home, in the space I’ve made for myself, in the routine that I’ve created to address my work (writing, editing, book life, and taking care of the dogs and cats). I’m content to text with my friends and set the phone down. This isn’t a knock on my friends or human interaction in general, just a truth about my identity. I am content being alone. But walking into the classroom and observing the students reminded me how important socialization is. How critical it is to interact with others in order to grow my perspective, challenge my norms, push me outside of the comfort zone. I’m better for it. Just like the students, I have to make time to “turn and talk”.

“Make the time to ‘turn and talk’.”

Second, I remembered immediately how much mental capacity is necessary to be a teacher. Goodness gracious. There’s creative work of designing the curriculum and making sure it’s got enough critical-thinking meat as well as age-appropriate relevance. Then there’s the creativity in doing the same for each class-period lesson. Then there’s the all-encompassing act of assessment, whether it's the informal observation in the classroom, the formative assignments, or the summative tasks to showcase skill growth, a teacher is always “on” both inside and outside of the classroom, and it’s exhausting. From the classroom management, to the planning and assessment for each learner, to the research—and while I didn’t have to attend all those meetings—there are all those meetings that really have nothing to do with the day-to-day job, but the bigger picture of teaching and learning.

I had a conversation with one of my former colleagues (yes, this is the school where I used to work full time before leaving to write full time) who expressed the day-to-day struggle. Having been teaching for fifteen years, *they indicated a sense of bone-weary exhaustion. Is it a wonder? The amount of mental capacity it takes to do the job coupled with the struggle of external perception that “teachers don’t do enough” along with administrations who add to the plate for “accountability” is not only disheartening, but drains the well dry.

When I sit down at my writing desk everyday, I feel joy. The act of creating, of telling a story or sharing my thoughts, is fulfilling. I might be poor, but I am so content doing this work. And while that creativity does draw from the well, this is a choice I make each day. I’m accountable to myself, to my own perception of what’s going to build and present my best work. This conversation with my colleague reminded me how unfulfilled I felt as a teacher. Don’t get me wrong, there were absolute moments of fulfillment. That moment when all the work that went into that unit and specific lesson hit all the right notes, when I got that student essay that nailed it, when I had a real conversation with a student that helped them through something, or the plethora of moments with colleagues when we laughed and planned and continued through the struggle together. But overall, my mind was always thinking about writing. Makes sense—it was what I was born to do. And that—time spent pursuing my passion—is so affirming.

“You canʻt ever go home again”

Finally, Thomas Wolfe in his 1940 novel by the same title wrote, “You can’t ever go home again.” I disagree with the sentiment. We need to go home again. It’s true that when we return home, we return with a new perspective, therefore we aren’t able to capture that experience with the sameness of our memories. It’s impossible because we are changed. New perspective allows you to see with new eyes, while at the same time grounding you to something familiar. Returning to my former school allowed me this renewal. I returned with three years of independent authorship and entrepreneurship added to my vitae, and while that impacted my experience of walking back into the classroom, being a teacher again offered me the familiar feeling of being good at something once more when authorship doesn’t provide that immediate feedback.

As I was standing in the hallway greeting students as they passed, welcoming my students to the classroom, one of the vice principals walked past. It was my last official day in the classroom, and we exchanged chatter about it. *They continued on, but then stopped and backtracked toward me once more. “I wanted to tell you,” they started and expounded about a teacher group I was a part of with them before I left. We reminisced about the power of that group, and the change we were able to enact because of our work. Then they said, “All that to say, you made a big difference in our school. Thank you.”

I don’t take compliments well. Never have (Iʻm sure there’s a bunch of psychology behind this), and I felt speechless. It was such a nice thing to say, and this person didn’t have to backtrack to offer it to me. I walked into the classroom, pondering it. I think perhaps I even attempted to discount it, but it couldn’t be dismissed. I had to take that sweet sentiment and allow it to bolster me. And it did. It reminded me that risk-taking for the greater good is a very important part of my identity. So perhaps you can’t go home again unchanged, but home often has a way of reaffirming ourselves and strengthening our purpose.

So, friends, I return to my writing desk full time, surrounded by my furry co-workers—Ruby, Haupia, Cheese, and Happy—ready to face the quiet of my writing life, excited to face it, and grateful for having taken the time away to refill the well in a different capacity.

A heads up:

I will be moving over to SubStack for additional content. While you’ll still have access to this weekly blog, perhaps consider subscribing to my substack for up-to-date news and additional writing excerpts meant to entertain.

*They denotes a singular person and is used to protect their identity.

Advice: Find your People

I was sitting in a high school classroom the other day listening to high school students chat with one another. They sat in clumps, computers open, phones out, some with masks and others without. Their conversations ranged from processing friendship drama to loud exuberance over a game they’d played the night before. Some begrudged the annoying dress code for an upcoming dance while others focused on an upcoming quiz in math. It made me think about my own experiences at that age and how important it felt to just be in the moment with one’s friends. How important it was to feel as if I had the opportunity to just be myself.

I was seventeen when this was taken.

Only, through my teenage years I never had been. It wasn’t like I didn’t like myself. I did. I just remember being afraid that other people might not like me. I was an introvert in disguise as an extrovert, a chameleon shifting colors to adapt to my needs. All I really wanted to do was be at home writing or reading. I remember feeling like other people wouldn’t be able to relate. They were fun and energetic. They did fun things, went to parties, had significant others. They wore stylish clothes and did well in classes. In hindsight, I was those things too. I didn’t have a boyfriend, but I had friends. Teachers liked me. I worked hard and did well. I was fun and laughed and was very conscious about how I presented myself. Though high school was mostly positive for me, I wouldn’t want to return to high school. College was where I finally began to feel comfortable in my own skin.

I read in this book—The Tattoo by Chris McKinney—about how each person has three suns around which they revolve. Those suns are family, friends, and a significant other. The main character of the book—Kenji—expresses that if two of those suns function in your life, then all’s good, but if two of them fail, you’re screwed. The point being: you must find your tribe.

Some of my favorite stories include the found family trope. The Aurora Cycle by Jay Kristoff and Amie Kaufman; The Six of Crows by Leigh Bardugo, The Raven Cycle by Maggie Steifvater, Fable by Adrienne Young, The House on the Cerulean Sea by TJ Klune. I love the idea of people finding their tribe. In the new story I’m working on, The Ring Academy: The Trials of Imogene Sol, Imogene’s found family is important as they help her clear her name of a horrible charge that could get her kicked out of the academy.

Coming August 1, 2023

I’m not exactly sure what this blog is about—maybe just a thought dump, but clearly, I’m thinking about “the tribe.” If I could offer a young person any sort of advice it would be that: Find your tribe.

February Ideals: Dreaming

Dear Friends,

I was sitting at the beach the other day, drinking my coffee, watching the ebb and flow of the waves as the tide came in. The sun was warm against my face, and I thought about how though life feels static, it really isn’t. I sat on that beach for nearly an hour, and recognized the tide coming in because waves came in, drew back out, came back in, cresting and washing over the shore until a rock was submerged under the water. It was exposed and dry when I arrived. The tide is subtle and if I hadn’t been paying attention, I might never have noticed it.

One of my dreams as an author is to be able to make a living creating. Am I there yet? Nope. Not even close. (Thank God for my husband, who’s supportive of this dream, my mom, who supplements me when she can, and for each of you, willing to buy the books when they drop. You all probably have multiple copies of each). While I might feel discouraged sometimes at how little impact my ripples are making in this giant ocean of writing and publishing books, as I sat on the shore watching the tide, I realized that what I’m doing isn’t static. There is a dynamic ebb and flow to it, moving me forward toward my goal.

It’s subtle.

So this February I’m going to remember that. The steps I take, the moves I make, the people I talk to, the list of things I have to do are all contributing to that rising tide. My job is just to keep doing what I do with a joyful heart filled with gratitude.

Thank you for being on this journey with me,

Cami

Click the button below for a link to a sample of my newsletter. Subscribe today!

My Top 10 Songs (w/Lyrics) 2021

I’ve mentioned I love music. There are probably lots of factors, but one is that I grew up around music. My grandfather and his three brothers sang professionally as a barbershop quartet in the 1950’s.

The House Brothers: Bill, David, Tom, and Dan (my grandpa).

One of the last times they sang together. From left to right, Tom, Bill, David and Dan.

My mom and her three sisters also sang together. My mom was in a band with my dad, and they were worship leaders at church. I grew up immersed in music, watching and listening to performances at every family gathering. Then I participated, spending time performing music with my parents and sister.

My mom and her sisters. From left to right: Terry (my mom), Danice, Susan and Judy.

As a writer, music contributes heavily to my writing process. When I sit down to work on a story, I make a playlist. The playlist is usually a mixture of music with lyrics and instrumental. Last year, Spotify informed me I spent over 85,000 minutes listening to music. That’s 16% of my year. Calculate it out into a day, it’s about 4 hours of my day. And if I’m only awake for an average of 16 hours a day, that calculates to more like 25% of my awake life is listening to music. That’s a lot of time.

I’m a moody listener. My tastes are often in a minor key. Lyrics are reflective, and I adore a vibe. One of my favorite things is to find “new” artists who are just getting started. It’s like unearthing a treasure (maybe a little like indie authors :).

So without further ado, this is the top ten songs I listened to this year starting with the most played. I filtered out the instrumental songs (because there were a ton) and kept it to only the ones with lyrics. Want to hear samples, hit up my Instagram stories. Want to hear them, look up my playlist on spotify “Top Ten Ten Times”. It has my top ten songs with lyrics for the last four years.

Happy Listening (please buy the artists’ music if you like it) and have an amazing CHRISTMAS!

Road to Echoes: 4 Lessons I Learned Writing Maxwell Wallace

I learned a lot about myself writing Maxwell Wallace. I’ve mentioned before that my ability to write female characters has been difficult and why that is (here), but Max is the first female character I’ve written fully formed without having to do much of anything. That was new for me, and I think a testament to the power of who she is as a character. So real. So alive.

When the Echo Answers is a companion novel to In the Echo of this Ghost Town

In honor of her, here are 4 things I learned from Max while writing this book:

Speak your mind

I grew up with the “be a good girl” lessons rooted in white, patriarchal, Christian home. I’m not disparaging my experience. I had a wonderful childhood with amazing parents and family, but this “good girl” expectation didn’t serve me when I walked out into the world without the safety net of my loving family. My naivety opened doors to major mishaps. If I’d been taught that my voice mattered equally, I wonder how things might have been different.

Cal, Maxwell’s dad, has taught her that her voice matters. That her voice is equal to everyone else and she doesn’t have to be “the good girl” but instead just a smart one. Maybe, on some level, this is the kind of girl I’d wished I’d been. Maybe Max can empower a young woman to find her voice, know her worth, and speak up (even when the expectations are to be a “good girl”). What I would tell that girl: You are still a good girl even when you speak up. SPEAK UP!

Don’t Apologize

Asking forgiveness is a good thing. That’s not what I mean when I say “don’t apologize.” Instead, this is referencing those apologies for existing, for having an opinion, for being different, or using your voice to care for yourself. It goes back to speaking up, but not feeling like your voice matters so you need to somehow disparage it by offering the “I’m sorry…”

Max doesn’t apologize unless she should. Goodness. Cal has taught her that she matters. And as she says in the book, “My father has shown me that everyday.” This!

Be Rude

One of my favorite podcasters—Crime Junkies—say this all the time. “It’s okay to be rude. Be rude. Stay alive.” Max is “rude” but maybe it isn’t so much as rude as assertive, confident, and self-assured. She knows her worth (even if she struggles sometimes, because don’t we all), but the lessons from her father lead her to the path of trusting herself. She says, “One of dad’s lessons: trust your instincts.”

I’ve gotten better at this, especially when it comes to my art. There’s this really great book I HIGHLY RECOMMEND to all creatives and especially women, and for women in general. Women Who Run With the Wolves: Myths and Stories of the Wild Woman Archetype by Clarissa Pinkola Estes, PhD. It’s a dense read, but ultimately, the idea is that as women we have shut down our intuition (due to all sorts of cultural and societal factors), but we need to reconnect to it. It is in our innate knowledge that we find the truth of our identity, our power, ourselves. It’s beautiful.

Don’t Hesitate. Just sit down

In the scene at the beginning when she sits down with Griffin outside the convenience store, Max says, “I leave the confines of the store and approach moody boy like he’s a wild animal in the zoo. Okay, too tentative. I actually just sit down. I don’t do too much with hesitancy and never have. Hesitancy hasn’t gotten me much, and besides, there isn’t time for it. Lessons from my father haven’t been about hanging back or blending into the background.”

I love this.

This lesson has so many applications. Whether it’s putting myself out there as an author with local bookstores, submitting that query to an agent, offering insight on my latest blog, or teaching a webinar, I can’t be hesitant. Sure, there’s a time to ponder and reflect to find the best plan of action, but then it’s time to commit. To step forward. To put myself on the line.

Max does this. I love it. I love her.

I hope you do too.